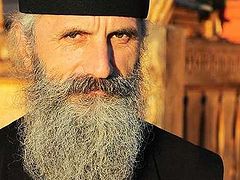

Our interviewee is Hieromonk Thaddeus (Pestov), the confessor for the brethren of the St. Nilus of Stolobny Hermitage.

—I have been in the St. Nilus Hermitage for twenty-six years now, as the confessor—more than fifteen years. I graduated from an agricultural college with a specialty in agronomy, and I worked a little in this field while studying at the St. Petersburg Agricultural University at the same time. When the question of initiation into the faith was finally resolved for me, with the blessing of one priest, I decided to go to a monastery to determine if I would stay or continue working in the world.

I haven’t changed monasteries since I arrived at the St. Nil Hermitage, although there have been offers to go to other places. I have clung to this monastery with all my heart. At that time, a new life for our country was beginning, the Christian faith was becoming available, and it drew me.

—In a monastery, the main thing is prayer, and in the world, everything is more successful with prayer. Why has the thirst for prayer weakened in people now, as compared to the beginning of their Church life, when they would read Akathists for hours, not tiring from dozens of prostrations? Today, for many, prayer is limited to when they go to church.

—The foundation of a Christian’s life, of course, is prayer—not just the keeping of God’s commandments, but also spiritual work on yourself. Our cooling towards prayer is probably because this work is the most difficult. It’s easier to shovel tons of coal or cut down the forest, but as soon as someone begins to pray, he starts to give up, to feel weak. And when he realizes this, when he understands his inability to overcome this infirmity, then he walks away. Maybe it’s because of faintheartedness or lack of faith, because he doesn’t turn to God enough, hoping in himself—”Why should I pray if I can cope myself, and I don’t even know if He’ll help or not?” But when problems and temptations begin, you remember God; you remember the words of the prayers.

—Does this happen with monks?

—In a monastery prayers are always being said, every day, day and night; a cooling towards it would be unnatural. The whole liturgical typikon presupposes the unceasing petitioning of God, in addition to which each of the brothers has his cell rule of prayer.

Chores and obediences do not replace prayer, but they are performed together, hand in hand. In obediences, the Jesus Prayer is the most well-known, in this sense universal, simple, and containing much of significance that is necessary for the salvation of man.

—Why do some passions we thought we had broken suddenly revive with new strength?

—I think it’s because the ones that have faded were not completely defeated. Perhaps someone settled down early and left off his spiritual work on himself—but, alas, the work ends only with death. If a man isn’t attentive to his inner life, then at the first temptation, all his passions will manifest themselves. A man who has abandoned or relaxed his spiritual life disarms himself. Prayer is a weapon that defeats both passions and sinful habits. Real monks, who have acquired dispassionateness, can be counted on your fingers. The passions live in all of us, but we monastics learn to restrain them or bring them to the point where they whither. It’s more difficult for a person in the world, being bound with worries, commotion, and cares.

There are those who lead a strict lifestyle in the world, but it’s thanks only to the same incessant struggle with themselves.

—“I have forgiven everyone who offended me, but my heart aches,” says a deeply believing man of prayer and fasting. What is the reason for this friction?

—This is said by a man who is still passionate. Our words and our deeds, coupled with the passions, defile a man. Yes, he has forgiven and isn’t holding a grudge, and even confesses his guilt, but his pride gives his heart no rest. In this case, you just have to endure, to humble yourself, and when the memory of an offense comes, try to drive it away from yourself. “Lord, Thou knowest the thoughts of my heart; do Thou Thyself rectify within me that which I have no strength to overcome.”

—To forget everything and not deal with the past—is this not an escape from reality and its problems?

—It’s normal for a reasonable, discerning man to try to examine a situation, so as not to fall into the same trap again. Only, in examining it, you have to seek the cause within yourself and justify your neighbor, not condemning him. This is the meaning of the Gospel commandment of love. Do no harm to others, because you don’t want it for yourself.

Offenses don’t simply topple a man. Either it’s a trial, or there were reasons for it on both sides. There is no man who has not sinned. A man can offend out of passion, out of habit, or out of carelessness. But as an Orthodox, I don’t have the right to judge him for it. I should understand him, forgive him, and work on myself. After all, it could have been allowed for my humility, for me to turn to God in prayer: “Lord, help me to endure these trials sent by Thee, and do Thou forgive my neighbor his sins.”

—Let’s say a loved one has passed away. Everything is understandable, but it’s painful and hard, especially for a mother who has buried her son. How can you overcome this resentment against God?

—Women in general are more prone to being guided by their emotions, and it is more difficult for them to overcome such losses. Here, only deep faith and the hope of meeting in the future life can help. If she is not certain that her son has found peace and beatitude, she should believe in the prayer of the Church, which is strong and able to save a person. Earthly life here is temporary, and it’s not necessary to grieve and weep over the loss of a loved one. She fulfilled her mission: She gave birth, reared, and released him to an independent life, and then—she has only to pray, help, and support, and prepare herself for eternity.

Pain is the distrust of God and His design.

—Why are there almost no high school students in church?

—Thirteen to twenty years old is the time for a conscious coming to God. Before that, young people live by the faith of their parents and grandparents. Then they are faced with a serious choice. Of course, this is about young people who are looking, thinking, and asking about the meaning of life. All the same, the modern world negatively affects young souls and leads them away from church, although faith remains in them.

If in childhood the parents laid down the basic concepts of good and evil and the foundations of the Christian faith, then they have nothing to fear; and at the right time, they have only to help their child overcome doubts—not teaching and commanding him, but trying to be closer.

—Is the fear of beginning a stricter life justified?

—If someone wants to lead a stricter lifestyle in the world, he must be guided by the advice and instructions of a spiritual father. It’s better not to do it yourself. If you have no spiritual father, then listen to priests who are close to you in spirit. As the Holy Fathers say, salvation is in much counsel, but with discernment.

St. Nilus of Stolobny Hermitage

St. Nilus of Stolobny Hermitage

—How can trust we’ve lost in a spiritual father be restored?

—If someone has a spiritual father, he should trust him fully. As one of the living fathers says, after God—there is only your spiritual father. Regardless of circumstances, priestly shortcomings, or the prejudices of this world, God imparts His blessing through the priest.

There is such a recommendation in monasticism: Before you find a spiritual father, you have to test whether his advice truly corresponds to Sacred Scripture. If it helps you, then you should adhere to him. If a priest’s words aren’t aligned with his deeds, then you should pray for the Lord to send you another.

—Should we endure financial and family problems, or should we fight for a better life?

—It’s not for nothing that they say a place does not save a man, but a man is saved in that place where the Lord put him. If you have the strength and opportunity, why not fight, move, change jobs? We are strangers on this earth.

It’s another matter when you can’t change anything and you have to accept circumstances as a given. You mustn’t lose courage, but turn to God, live the spiritual life, and enjoy those blessings that you have at the moment.

Christ teaches us to love God and neighbor, to fulfill the commandments—no one has or will abolish this until the end of his earthly life. Everything else is temporary, but we must do what depends on us.

—What should a parish community look like?

—The most ideal community is a monastery: people united by the same aspiration, living by the same spirit. Monasteries have always been models for the laity too. You won’t find any new templates.