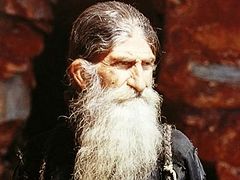

Archimandrite Pavlos. Photo: Facebook “Friends of Mount Sinai Monastery”

Archimandrite Pavlos. Photo: Facebook “Friends of Mount Sinai Monastery”

There are people with whom you’ve spoken only a little but you’ll preserve their light in your heart forever. Recalling their righteousness, you strive for it yourself. Fr. Pavlos, seen by many pilgrims as he led excursions on Mt. Sinai, was an earthly angel. He had everything—truth, joy, humility, purity. Your soul was warmed being near him. All intellectuality and cleverness fell away, like a husk, and you could clearly see where is light and where darkness.

Archimandrite Pavlos (in the world George Bougiouras) was born January 16, 1939 in Kranidi in the Peloponnese, to a pious family. He worked in the Evangelismos Hospital in Athens. After graduating from the theological department of the University of Athens in 1972, he left for St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mt. Sinai, where he was tonsured in monasticism and ordained. He was the confessor of the monastery for forty-eight years, and was a member of the monastery synaxis, second in rank after the abbot, Archbishop Damianos of Raithu and Sinai. Fr. Pavlos was a strict ascetic, man of prayer, a hard worker, and merciful to all, especially to the Bedouins living around the monastery. He reposed on March 1, 2020.

We met in the summer of 2007. I was working in the monastery library. One day after Liturgy I went up to the guest house to drink coffee. Fr. Pavlos was thrilled to learn that I was from Russia. He had recently returned from there himself, from a pilgrimage: “Can you imagine? The plane landed, and all around—forest, fields, everything green…” Indeed, after spending a week on Mt. Sinai, in the severe austerity of its rocky attire, you look at the joy that the blooming Russian nature gives us in a different way!

Fr. Pavlos was inconspicuous and irreplaceable. He was constantly on the move: sweeping the yard, cleaning the church, washing, leading tours for pilgrims. He was the first to come to church and the last to leave, like a simple monk. But he was a significant figure—the spiritual father of the Sinai Monastery: Clergy and laity from all ends of the earth came to him every day for confession. When I was preparing to confess in Greek for the first time, my neighbors in the guest house, relatives of the monks, reassured me: “Don’t be afraid! Fr. Pavlos advises little; more than advising he prays for you and always says: ‘Don’t judge!’” I went to the confessional on the appointed day and hour. Fr. Pavlos had lively eyes and a quiet heart. He said a prayer, asked how I believe—I read the Nicene Creed—and he heard my confession. Batiushka prayed and at the end quietly asked: “Remember: all our troubles are due to the fact that we judge not ourselves, but other people. Judge no one!” Such humble love came from the Elder (he sincerely considers himself worse than me!), that this love of his heals and revives the soul.

Services begin at 4:00 in the morning on Mt. Sinai. The first days, I easily got up, and then, although I arrived at the beginning, I would nod off to the monotone reading of the Psalms and the canon. I lamented about it. Batiushka rejoiced like a child: “You are sleeping among the saints! But still, come!”

Fr. Pavlos loves God and is afraid of offending Him even a little. I had already been staying on Mt. Sinai for a while but had never been to the summit: I was ashamed to trouble the monks and ask for a guide. One evening I found out that pilgrims from Thessaloniki were going to be serving the Liturgy at the top at night, and I could go with them and receive Communion. In place of joy came vexation: At lunch they brought us eggs, a rare food for these places… usually it’s vegetables… but I didn’t know then that there would be Liturgy that night… In my thoughts I dialed the number of Fr. Pavlos’ cell and I heard in response: “Alexandra, you will offend God with such Communion, and you won’t bring yourself any benefit. You have to fast for at least a day before Communion for the Lord’s sake.[1] Go, pray, and you’ll return in joy. But you’ll commune in the monastery, having prepared yourself.” Hearing these words from someone else, I would have been upset—but from him they sounded like they’ were from the mouth of Christ!

Fr. Pavlos reposed on the morning of Forgiveness Sunday. One of his Mt. Sinai brothers said: “His prayer was such that if the altar were to go up in flames right now, he wouldn’t notice! I believe that Geronda will not abandon his beloved work—communion with God—and that he will pray for us in the Heavenly Kingdom! He who comforted men all his life will now himself receive great consolation from God!”

Fr. Pavlos has no written legacy. Therefore, the only thing that remains is his oral conversations with pilgrims to Mt. Sinai and on television and radio programs on Crete and Cyprus. Here are several of his spiritual counsels.

Archimandrite Pavlos of Mt. Sinai

Non-judgment, prayer, and a pure heart are the foundation for spiritual work

Archimandrite Pavlos (Bougiouras). Photo: Facebook “Friends of Mount Sinai Monastery”

Archimandrite Pavlos (Bougiouras). Photo: Facebook “Friends of Mount Sinai Monastery”

The name of God is great power! As are the words that we monks say: “Lord Jesus Christ have mercy on me.” If you say them from your whole heart, and you labor and preserve your heart in purity, they will have great power. A simple example: We often lose something. The evil one makes us nervous and irritated: “Come on, where did I put it?” Don’t make a fuss, but say: “Lord, Jesus Christ, show me what I lost.” And He will show you.

Prayer is a great consolation in all temptations and trials in life. It is an invincible weapon. Therefore, the enemy frightfully rises up against prayer and tries to take it away from a man by any means. When we pray in church and our mind is dissipated, we need to bring it back: “Where are you going? Come back!” And watch after the purity of your heart, because the purer the heart, the easier it is to reach Christ. The great ascetics reached great heights, but this was preceded by their podvig of purifying the soul from the passions. The passions, like clouds in the sky, conceal the light and it becomes dark.

In confession, we often say: “I don’t have any special sins… they’re normal…” And among them is condemnation, which is a heavy sin. We consider it “normal.” Condemnation is a spiritual disaster. Non-condemnation was laid at the foundation of the podvig of all those who have succeeded spiritually. The Desert Fathers tried to cultivate the virtue of non-condemnation. They condemned no one; they were very afraid to condemn. St. John Climacus says: “A monk who does not condemn goes to another monk’s cell and sees it dirty and cluttered. And what does he say? Ah, this brother is engaged in spiritual work, and he has no time for himself. Then he goes to another’s cell, and there it’s clean and everything is tidy. He thinks: This brother has the same purity within as he has in his cell.” He didn’t condemn either of them. But we, in our carelessness, could have condemned both.

Christ very wisely said: Judge not, and ye shall not be judged (Lk. 6:37). And we easily lose non-condemnation and often justify ourselves: “I said it out of love!” It’s not love! The great ascetic St. Isaac the Syrian says: “On that day when you open your mouth and condemn your brother, all the good you have done will be lost.” So strong! If we are attentive to ourselves, we will see the fruits of non-condemnation.

Non-condemnation, prayer, and purity of heart are the foundation upon which spiritual work is built.

The greatest consolation is the acquisition of peace in the soul

—Tell us about the Divine consolation that life on Mt. Sinai brings.

—We need to be simpler. A child, simple by nature, rejoices in everything. Everything pleases him. He has no problems. And if someone grows up and remains a child in his soul, he lives wonderfully! He who does not judge knows that non-condemnation brings peace to the soul. When a man has peace within himself, he also has great consolation! Therefore, it’s no accident that the Church prays at every service: “Again and again in peace let us pray to the Lord,” “For the peace from above … let us pray to the Lord.” We lose peace through inattentiveness. And even we monks get distracted. But if we manage to remain as simple as children in our souls, to not condemn, to pray, and to have peace in our souls and live in the presence of God, then this is the greatest comfort.

A spiritual man never loses hope

—We often hear: “spirit-bearing man,” “spiritual”—how do we understand these? Are there such people today?

—For secular people, this is a person of great knowledge, an inspired person—in a word, “intelligentsia.” For us, for believers, for those who labor in good podvigs in Christ, it is the man who has become a temple of the Holy Spirit, His dwelling place. That is, literally a “spirit-bearing person”—he who bears the Holy Spirit within himself. By boundless Divine love, the Holy Spirit takes up abode in a man. Such a man experientially knows the grace-giving properties of the Holy Spirit: peace of mind, love, long-suffering, faith, hope, which he will never lose. Despondency and hopelessness are completely alien and incomprehensible for him.

A person who is “spiritual” in the worldly sense of the word can despair, that is, lose hope (we have the examples of poets who committed suicide at a young age). For us, it is not this way, because hope is the fruit of the Holy Spirit, Who has lifegiving power and gives us life.

Archimandrite Pavlos. Photo: Facebook “Friends of Mount Sinai Monastery”

Archimandrite Pavlos. Photo: Facebook “Friends of Mount Sinai Monastery”

The main difference between the understanding of “spirituality” in the worldly and Christian senses is that a Christian experiences the acquisition of the Holy Spirit and His gifts and connects his life with the life of the Holy Spirit. A secular person can be called “spiritual,” but he in no way connects his life with the Holy Spirit.

The acquisition of the Holy Spirit also manifests outwardly: Such a person has a collected mind, simplicity of reasoning, and expresses his thoughts in few words and deeply, like the Holy Fathers. After all, the words of the Holy Fathers are very rich, especially in the patericons: what deep thoughts they express in short sentences! Therefore, the patericons do not wear us out, but are pleasant to read.

A spiritual person experiences the presence of the Holy Spirit. He receives His gifts: sanctification, a pure life, love, hope, faith; and often the gift of clairvoyance—being enlightened by the Holy Spirit, he sees what may happen in the future.

And there are such people today.

—How can we become a spiritual person and acquire the gifts of the Holy Spirit? Is there a recipe?

—Of course—it’s the spiritual recipe given to us by Christ. The Apostles, the Fathers of the Church, and the saints followed it. The Church recorded it in the sacred books, in the patericons, in the canons of the Ecumenical Councils, in its daily life. And everyone can act according to it and see its effect on themselves.

The goal of an Orthodox Christian is the acquisition of the Holy Spirit. To become a good person is not the goal, and there are very good people outside of Christianity. To become a spirit-bearing person, to receive the Holy Spirit within yourself, is something different. The main thing is to purify yourself from the passions, because the Holy Spirit cannot enter into a heart polluted by them. There is no nationalism in Orthodoxy—there is neither Greek, nor Jew. What’s important is how much you’ve liberated yourself from the passions.

The Holy Spirit seeks a pure heart and takes up abode within it. Such a person lives continually in the presence of the Holy Spirit: He finds inner silence and reconciles himself, first of all, with God, and with himself and others. He who has a pure heart does not divide people into good and bad. What’s important to him is not “real reality,” but “spiritual reality.” He hopes to be saved. He never despairs, does not lose hope in difficult circumstances. Such is a grace-filled, spirit-bearing person.

Labor such that they will write a life about you

—How should I be if I don’t know the life of my saint?

—If someone doesn’t know the life of his saint, I advise him to labor such that they will write a life about him, and his name will be inscribed with the saints.

The choice of marriage or celibacy is everyone’s inner choice

—Are monasticism and marriage different paths with one goal, or are they really one path?

—One spiritual man said that there are two crosses: the cross of marriage and the cross of celibacy, that is, the monastic life. Another added that there is a third cross—of childlessness in marriage. Choosing a path is an internal matter for every man. No one will tell you what’s better for you: to become a monk or get married.

—How can we make this choice; how can we find out where our calling is—in marriage or monasticism?

—The person himself, within himself, understands which is his path and which isn’t. It’s easy! But the choice must be made independently; it’s everyone’s personal decision. A man himself determines: “Monasticism is not for me; I want to start a family.” Such a person could go to a monastery and become a novice, and eventually leave. It means the monastic life is not for him. God doesn’t violate our freedom. He sees what a man is inclined towards and strengthens him on this path.

It is necessary to have a dissimilarity of characters in marriage

—How much should we endure in marriage?

—If you chose the path of marriage and have united with another person in the Sacrament, which is called great, you must carry the cross to the end. When a priest or hieromonk removes his riassa and goes into the world, people don’t like it. And it’s truly hard! When someone gets divorced and leaves his family, it’s now considered normal; as well as concluding second and third marriages… But the priesthood is a Sacrament, and marriage is also a great Sacrament! And suddenly one of the spouses leaves to “fix” his life. What do you mean “fix?” In fact, in the end it will be worse for both: more problems rather than “fixing” your life. And if there are children, they will suffer spiritually and mentally. They will have psychological problems. It does not happen that children don’t suffer during a divorce.

We don’t know how to humble ourselves and say: “If everything doesn’t go as I want, I accept the situation as it is.” He that endureth to the end shall be saved (Mt. 10:22). And this is where real love manifests itself, especially in marriage. Often in a family, two people have completely different characters: One is irascible, the other meek. And the Lord unites two such opposites.

It’s a big mistake to say: “We have such different personalities!” Spouses often break up for this reason. But that’s how it is by nature—that people have different characters. The wife has one character and the husband another. A similarity of characters is something unnatural. We need dissimilarity! But both patience and love in Christ are necessary, and deep humility as the foundation of our life. An egotist thinks he’s the only one who offers something, not the other; that he is the center of life. The humble man thinks he is lower than everyone, and thus ascends to Heaven. It is only through patience, humility, and love that we can “conquer” another person.

—That is, the monastic virtues—love, humility, gentleness, patience, podvig—are necessary in marriage?

—Yes; therefore that ascetic spoke of two crosses: marriage and celibacy. People carry a cross in both.

—What is the meaning of such a life?

—To live according to the will of God and do His will, and to understand that it was no accident that I wound up with this person. The Lord knows why he united these people; to feel your life going according to the providence of God.

No one is saved without temptations

—Why are there so many temptations in fasting?

—In the Patericon, one holy elder says: “If we remove temptations from our lives, no one will be saved!” The Lord doesn’t send us temptations. He allows them for our own good. Temptations are unpleasant for us, but they help move us forward. Without them, a person cannot become spiritual. Thanks to them, we stand up to fight against evil, against sin, and we begin to pray. Temptations awaken us from sleep.

Elder Paisios says that temptations are necessary to cultivate a good mind. We may think, “He hates me.” Don’t think like this! How does he hate you? Man is not created for hatred. Remember that our enemy is our benefactor. He who does us harm causes us to turn to God. According to St. John Chrysostom: “There are no offending people; there are only those who are offended.”

Why has my child become unbearable?

—My child has become unbearable. He comes home at night, and I can’t cope with him… How can we raise children so this won’t happen?

—Here we, the older ones, can be too categorical and shift the blame to our children. We should remember what we were like at their age! How did we behave? Remember your “achievements.” Especially since today’s parents are sometimes more occupied with what to eat and how to dress than with prayer.

Cell phones steal our freedom in life

—We are very concerned about the issue of the “seal of the antichrist.” What should we do to not accept it?

—Has that moment that the Sacred Scriptures tell us about in the Apocalypse really come already? It clearly says there that some will believe in the antichrist and follow after him and receive the mark on the hand and the forehead. Has this really happened already? When this hour comes, our faith will be revealed. We will have to say then: No.

If only man were not so closely bound to things and comfort! Half of Greece—no, probably three quarters—is gathered in Athens today! We’re all Athenians now. People have left the beauty of Greece—its seas and mountains. In the villages, we slept under pine trees and our lungs were full of oxygen. We were the happiest people in the world! This is no more. My father and I went to our plot of land and spent the night there—in the mountains, in the quietness. It was a paradisiacal sleep—in the fragrance of pines and thyme! That was life! Now we’re all crammed into Attica for so-called “comfort.” Is that really comfort?!

Every child already has a cell phone now. Either we buy them or we give them money to buy them. We pester them not to lose it. But is a telephone really so vital? After all, it’s not only the radiation (cell phones harm people physically), but the main thing is that a phone deprives your soul of peace. Wherever you go, you have your phone with you. There’s no freedom left in your life. And this is a true “seal.”

A Christian always tells the truth

—Lying to save yourself under certain circumstances—is it good or is it a sin?

—You shouldn’t justify yourself by your circumstances. A faithful Christian should always speak the truth. Maybe once or twice in your life there will be “circumstances” for a lie: Someone is chasing someone in order to kill him, and you hide him at your place, and, of course, you’re not going to say: “Come in, here he is!”

—And if someone is terminally ill, does he always have to tell the truth?

—Something happened with me one time when I was working in Evangelismos Hospital. One day I was called to go visit a dying woman. The sisters came and said, “She wants to talk to you.” The woman was in the throes of death. She was fifty; not old yet. And she said: “Why did they hide the truth from me?” She had cancer… Her illness lasted for a long time; I don’t remember how long now. They didn’t tell her anything. She could have been preparing herself during this time, including spiritually!

People don’t die. They fall asleep until the Second Coming

—What do the reposed need most of all—to be commemorated at memorial services, panikhidas at their graves, or alms on their behalf?

—First of all, we shouldn’t call them dead, but asleep. The first Christians didn’t call the burial places of the dead “graves,” but resting places,[2] because the person didn’t die, but fell asleep.

The thing that helps our reposed the most is the Divine Liturgy. When a priest serves the proskomidia and takes out the particles for the reposed, this is the most important thing. Alms also help the soul of the reposed.

But there’s another thing that really helps—the attitude of our soul to God. For example, if a loved one leaves too early—a brother, a child, some accident occurs—we must never attribute what happened to God. This thought weighs on the soul. St. Anastasius of Sinai, a great saint, who became the Patriarch of Antioch, says that the soul can leave this world pure, and we torment it with our questioning God: Why? Why did God take this person from us? This harms your soul! It’s better to say: “My God, Thou gavest this person life, and Thou didst take it away. Thou didst move as Thou didst desire”—resembling the much-suffering Job—“blessed be the name of the Lord!”

—What happens to a person after death?

—Those who live in sin on earth already taste hell here. What do you think? Life in sin—that’s hell. Those who live in faith taste Paradise already in this life. That is, even before the final judgment some taste hell, and others Paradise. And after the Second Coming we will finally partake of the glory of God—or the opposite (may the Lord not allow this to happen to any of us!).

If you can’t fast bodily, fast verbally

—I can’t fast because I’m sick. Can I commune without fasting?

—If there is a serious reason why you can’t abstain from non-fasting food, observe a different fast—verbal. Watch what comes out from your heart, from the depths of your soul, because this is what contaminates most of all. Try not to talk too much, not to condemn others. This will be the greatest fast for you. The Church doesn’t want to harm someone, and if he can’t fast, what should he do now, die? The Church is like a mother. But he who truly can fast—let him not seek excuses for himself. Don’t slander, don’t gossip, don’t upset anyone with your words—this is your fast, and you’ll commune with a pure heart.

What matters isn’t how often you commune, but how you commune

Archimandrite Pavlos. Photo: Facebook “Friends of Mount Sinai Monastery” —What do you think about frequent Communion?

Archimandrite Pavlos. Photo: Facebook “Friends of Mount Sinai Monastery” —What do you think about frequent Communion?

—The question about Holy Communion is not how often you commune, but how you commune. If we approach unprepared, then the Apostle Paul says: “Many of you are sick and die because you commune unworthily” (cf. 1 Cor. 11:29-30). Therefore, the first thing someone coming to Communion should carefully examine is whether he’s receiving the Body and Blood of Christ worthily. It’s not time that makes someone worthy of Communion, because he who is worthy—says St. John Chrysostom—can commune daily. But he who is unworthy cannot commune even once a year. You mustn’t say: I’ve communed four times this year, so everything’s fine. If you love God, will four, five, or six times a year really be enough? The number of times you commune is still disproportionate to the boundless love of God.

—During a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, we were blessed to commune at all the holy sites. Is this a sin?

—Everyone should examine himself, whether he’s worthy to commune or not. That’s not my opinion—it’s what the Sacred Scriptures say: Everyone should examine himself when communing of the Body and Blood of Christ. We don’t become worthy just because we’re in the Holy Land or on Mt. Sinai. We have to be very attentive in preparing for Communion!

—How can we understand if we’re worthy or not?

—There’s a simple Church rule: You go to the priest in confession and ask. If he gives you a blessing for Communion, don’t doubt it. After that, the responsibility is on him. If the priest made a mistake, he will answer before God. But the believer who asked and humbled himself before the answer is calm. For a priest, this is really the most difficult thing—that people would be able to open their hearts to him. It’s the spilling of blood.

On the meaning of the parable of the Good Samaritan

—The parable of the Good Samaritan tells of a wounded man and about how a priest passed him by. Should we, the wounded, expect something from our priest or not?

—This Gospel passage has a symbolic meaning. Who is this priest who was indifferent to this man? Who is the Good Samaritan who bandaged the wounds of the man who fell into the hands of robbers? Let’s look at how the Holy Fathers interpreted this passage.

As far as my meager knowledge allows, the Good Samaritan in this parable is Christ, Who helped when others passed by—both a priest (a Jewish priest of the pre-Christian period), and a Pharisee (who testified to his virtue more often in word than in deed). They did not pity the bleeding man. Christ took pity upon him. He took him to the hospital and gave two denarii. What are these two denarii? The two Testaments—the Old and New. And He said if you need anything else, I’ll return. His measure of love is high!

Of course, we can’t transfer this to today and say that can’t expect anything charitable from our priests. Many of our priests do acts of charity, visiting hospitals, for example. Many also remain indifferent. I’m probably indifferent sometimes too. But there are priests who sacrifice themselves for the sake of others. One priest in Athens would gather scrap paper, sell it, and use the money to help orphaned children. Therefore, we have to be careful when interpreting the words of the Gospel.

We were not created for death. We were created to live eternally

—In the monasteries, the monastics regularly visit cemeteries and ossuaries “in order to keep a remembrance of death.” What is the need for the remembrance of death?

—Man is at death’s door from the day of his birth. He doesn’t know when this life will end for him. A very young man gets into an accident and departs this life. We get on a train or a plane and we don’t know if we’ll reach our destination. We don’t know if we’ll be alive tomorrow. Therefore, the remembrance of death (don’t confuse it with the memory of the last times and of the antichrist) is a reality: We all truly are on the threshold of death.

—So then why should we study, work, live?

—The remembrance of death is creative. If I think that tomorrow I could die and I will have to answer for all that I’ve done, it will bring me not turmoil and hopelessness, but joy that I will live eternally. I was not created for this life on Earth, but for another. The fear of death helps me grow spiritually and gives my soul peace.

—Do you fear death?

—I fear it a little, to be honest. This fear is inherent in our nature: We were not created for death. We were created to live eternally. That’s how the Lord created us. Sin made us mortal. I have some “sinful accomplishments,” and, of course, I confessed them, repented, but as a man I am afraid. Those who have attained the highest spiritual measure—holiness—do not fear death. I hope that death will unite me with Christ.