The Sretensky Monastery publishing house is preparing a book by Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov). It contains true stories that took place during different years, which were later used in the author's sermons.

|

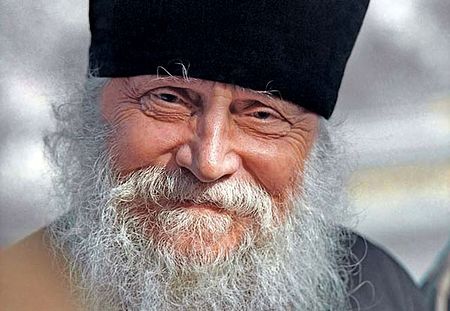

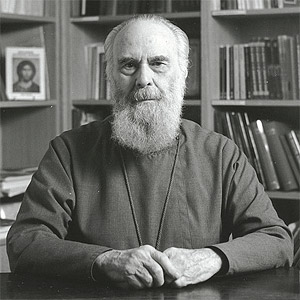

| Bishop Basil (Rodzianko). Photo by Yuri Kaver. |

In fact, Vladyka Basil had finally reached the hour when he would embark upon the journey for which he had prepared himself all his life. Vladyka often tried to tell people about it, but no one understood him. They preferred to let his words go in one ear and out the other, or sympathetically play back the usual platitudes, like, “Oh, what are you saying, Vladyka? You’ll be alive for a long time yet! God is merciful…” Vladyka, however, sought a foretaste of this journey with great impatience and lively interest.

In general, he was an avid traveler even during his lifetime. I would even say that traveling was his true calling, and even his way of life.

He no doubt began his journey in 1915, when he came into the world as the infant who would later become Bishop Basil, at his family estate called Otrada. The newborn was named Vladimir. His grandfather on his father’s side was the chairman of the State Duma of the Russian Empire, Mikhail Vladimirovich Rodzianko. His mother came from the old princely families Golitsyn and Sumarokov. If fact, many famous Russian noble families were either closely related to, or simply became close to this newly born slave of God.

Vladyka began his next serious journey in 1920, when he was five years old. It was a long road, by land and by sea, through Turkey and Greece to Serbia. The decision to take this journey was involuntary—the new regime had no intention of allowing the family of the former chairman of the State Duma to remain among the living. The Rodziankos settled in Belgrad, where the future bishop grew up.

|

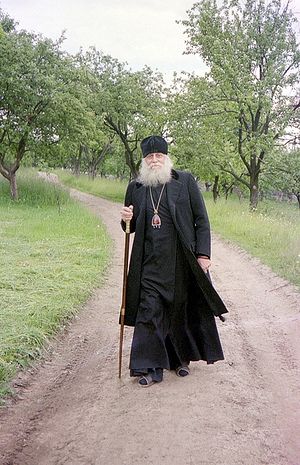

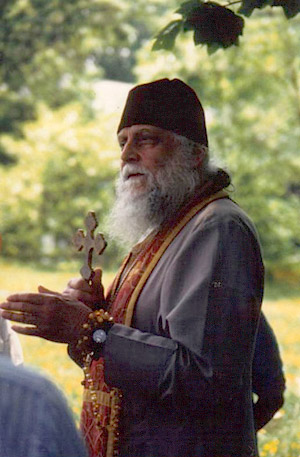

| Vladyka Basil in Pochaev. Photo by the author. |

However, even before these Vladyka had a no less important teacher, whom he would remember all the rest of his life. This was his tutor—a former officer of the White Army. No one but little Volodya knew that this tutor beat and tortured the boy, doing it in such a careful way as not to leave any marks. The thing is that this wretched, fierce officer hated Mikhail Vasilievch Rodzianko with the darkest hatred. He considered the boy’s grandfather to be the cause of Russia’s downfall. Because he could not bring himself to vent his anger upon the grandfather, the grandson had to pay.

Many years later, Vladyka recalled, “Not long before her death, my mother said, ‘Forgive me for allowing him to torment you through my negligence when you were a child.’ ‘Mama, it happened by God’s Providence,’ I answered. If that had not happened during my childhood years, I would not have become what I am today…’”

When Vladyka was already an aged man, the Lord led him in one of his journeys to Tsarskoe Selo. Vladyka was blessed to serve the Liturgy in the church of the Feodorovskaya icon of the Mother of God—the church which was particularly cared for by Emperor Nicholas II, and which the whole royal family loved. When the service was over, Vladyka went out to the people and repented for the guilt that he had so acutely felt from his very childhood, only because he was the grandson of his beloved grandfather. Vladyka said then:

“My grandfather wanted only what was best for Russia, but as a weak human being, he often made mistakes. He was mistaken when he sent the members of parliament to the Emperor to request for his abdication. He did not think that His Highness would abdicate for himself and for his son. When he learned of it, he wept bitterly, saying, “Now there is nothing to be done. Now Russia has perished.” He became the involuntary cause of the tragedy in Ekaterinburg. This was an involuntary sin, but a sin nonetheless. And now, in this holy place, I ask forgiveness for my grandfather and for myself before Russia, before her people, and before the royal family; and as a bishop vested with the authority, I forgive and absolve his soul of this involuntary sin.

|

| The Feodorov Cathedral in Tsarskoe Selo. Photo by uolliss.ya.ru. |

They did not execute him, but they did send him to prison camp—for eight years. Tito’s camps were no less horrifying than those in the USSR. Fortunately, however, Tito and Stalin had a falling out, and in order to insult at least some way his former patron, Tito released all the Russian emigrants from the Yugoslav prisons. Thus, Vladyka was in the Yugoslavian prison only two years (or, perhaps it would be better to say, two whole years). After prison, he again began his journeying.

|

| Priest Vladimir Rodzianko at the BBC studio. |

Years passed, and Fr. Vladimir became a widower. The Church blessed him to receive the monastic tonsure, at which he received the new name, Basil, and the rank of bishop. At this, bishop Basil set off upon yet another journey—to America. There, the new bishop brought thousands of Protestants, Catholics, and simply non-religious people to the Orthodox faith. But as it often happens, he turned out to be “superfluous”; not so much because of his energetic activity as for his straightforward opposition to one powerful, but absolutely unacceptable group in the Church—a “lobby,” as they say. As a result, His Eminence Basil was sent into “retirement”; that is, an unpaid, indefinite leave without any means of support or care.

But Vladyka Basil, who, as the Church teaches and his already amassed life experience showed, saw God’s Providence in even this uninspiring event, and it became no more than a continuation of his heart’s desire for new ascetic labors and accomplishments. During those years it was just becoming possible to travel to Russia. This was Vladyka’s long-cherished and passionate dream, and he ecstatically set off for his sacred, native land.

There are a few incidents that took place during that time, to which I had the opportunity to be a witness.

Vladyka Basil appeared in my life and the life of my friend, the sculptor Viacheslav Mikhailovich Klykov, as an amazing, unexpected joy.

It happened in 1987. The memorable anniversary of the murder of the Royal family, July 17, was approaching. Viacheslav Mikhailovich and I wanted very much to served a pannikhida for the Tsar, but that was not so easy to do in those days. It was unthinkable to simply go to a church in Moscow and ask a priest to serve a pannikhida for the reposed Nicholas II. Everyone understood quite well that this would become known, and the priest would be beset with problems afterward—the least of which would be the relinquishing of his position at his parish. Neither did we wish to serve a pannikhida at home, because too many of our friends wanted to come.

|

| Sculptor Viacheslav Klykov, hieromonk Tikhon (Shevkunov) and Bishop Basil. |

Suddenly, I had a thought: since the government had already granted official permission to consecrate the grave-coverings of Peresvet and Oslyabya, we could serve a pannikhida to the royal family during the consecration. Of course, the authorities would definitely send an observer, but that spy would hardly be able to make sense of those liturgical subtleties; for them it would just be a long, incomprehensible Church service.

Viacheslav Mikhailovich liked this idea very much. It remained only to find a priest who would agree to take the risk—for there were risks, after all, however minor they may have been. But if one of the spies should figure out what was actually happening, then… Well, we didn’t really want to think about that. Just the same, we did not want to subject any of our clergyman friends to danger.

Then, someone told us that Bishop Basil (Rodzianko) had flown in from America. Many of us had heard about this bishop, and had heard about his Church radio programs on “the voice of the enemy.” After talking it over, we came to the conclusion that a better candidate to serve a pannikhida for the royal family could not be found. First of all, he was a White Army guard. Secondly, as a foreigner his risk was minimal—in any case, less than it would be for one of our priests. The KGB would not be able to do much to him. In any case, it would be easier for him to get out of trouble, being an American, as we convinced ourselves. In general, as one cynical but popular song of that time went, “Grandpa is old, and it’s all the same to him.” Finally, we simply had no other option!

|

| Bishop Basil (Rodzianko). Photo by the author. |

Vladyka came out to the hotel lobby to meet us… and we were conquered! Before us stood an unusually stately, tall elderly man with an amazingly kind face. To be more precise, and without any irony or sentimentalism, he was a “noble elder,” as they used to say in olden times. We hadn’t seen such bishops before. In him we could get a glimpse of another Russia, a completely different culture, and different sort of hierarch from those to whom we had been previously exposed. Not that ours were worse—no! But he was certainly a completely different hierarch!

Viacheslav Mikhailovich and I were immediately ashamed that we had conspired to subject him—such a large, kind, defenseless, and trusting man—to danger. After our first acquaintance and a few general words, without having yet touched upon the main theme, we excused ourselves, and went off to the side to whisper. We unanimously agreed to insist that Vladyka carefully think it over before accepting our proposal.

The three of us went outside the hotel for a stroll, a good distance from the hotel microphones. As soon as Vladyka heard the reason for our visit, he became literally ecstatic, stopped in the middle of the sidewalk, and grabbed my arm as if I might run away, expressing not only his agreement, but passionately assuring us that we had been sent by the Lord God Himself! As I stood rubbing my elbow, staring at Vladyka in fright, wondering if the bruise under my shirt was a large one, it all became clear. It turns out that for fifty years, from the time he became a priest, Vladyka Basil had served unfailingly, every year, a memorial service for the royal family on that date. This year, having arrived in Moscow, he had been agonizing daily over where and how he could serve that pannikhida in the Soviet Union. Then we showed up with our pious scheme. Vladyka saw us as angels sent from heaven, no more no less! At our earnest warnings about the danger he only waived his hand in annoyance.

Only a few questions remained on our minds, which Vladyka Basil resolved somehow, very quickly. According to ancient Church canons, a bishop who goes to another diocese cannot conduct services without the blessing of the local ruling hierarch, and in Moscow, that meant the Patriarch himself. Vladyka told us that just the evening before, His Holiness Patriarch Pimen had given him permission to serve in Moscow what are called “personal needs,” that is, molebens and pannikhidas. That was just what we needed. We also needed a choir. It so happened that nearly all the pilgrims who had come with Vladyka sang in church choirs.

|

| The grave coverings of Peresvet and Oslyabya, the work of sculptor Viacheslav Klykov. |

Representatives of the factory management and a few other morose individuals accompanied us through a long corridor towards the place where Peresvet and Oslyabya are buried. My heart stopped when I saw that the comrades in civilian suits were glaring suspiciously at the stately hierarch and his frightened, silent flock, who nevertheless looked just like soviet people. But it all worked out.

Klykov’s grave covering for Peresvet and Osliabya really was unusually beautiful—ascetically austere and grand. We began with the consecration, and then, as we had agreed, we slid unnoticeably to the officials into the pannikhida. Vladyka served with such feeling, and his parishioners sang so self-forgettingly, that it all seemed to last but a moment! Vladyka did not pronounce the word “emperor,” “empress,” or “tsarevich” but simply commemorated at first the warriors Adrian Oslyabya and Alexander Peresvet, then “slain Nicholai, slain Alexandra, slain child Alexy, slain maidens Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and child Anastasia,” as well as the names of his and our reposed relatives and friends.

Who knows? Perhaps those sent to watch us understood it all? I suspect that they did. But no one gave it away. They thanked us as they saw us off, and it seemed to me and Viacheslav Mikhailovich that they were sincere.

When we went out of the factory lobby and found ourselves in the city once again, Vladyka Basil suddenly came up to me gave me a big hug. Then he pronounced the words which have remained in my memory ever since. He said that he would be thankful to me to the end of his life for what I did for him today. Although I couldn’t understand at all what I had done, his words were very pleasant to me.

Truly, Vladyka related to me with great kindness all the rest of his life, and that became one of my most treasured yet undeserved gifts of God.

In those years, the truth about the Tsar-Passion Bearer and his family was only beginning to come out. Books brought from outside the country, stories told by the older generation of Orthodox believers—that is how we found out about the new martyrs and confessors of Russia.

|

| The holy Passion Bearers. An icon painted by the sisters of the New Tikhvin Monastery. |

This was all happening during one of the most difficult periods of my life. Still a novice, (not yet a tonsured monk), I dragged myself to the grave of Patriarch Tikhon at Donskoi Monastery in a most unenviable state of mind. It was the day of the murder of the royal family. That year, pannikhidas were being served for them unconcealed. I began to ask the Royal Martyrs with all my heart that, if they have boldness before God, they would help me.

The pannikhida ended. I left the church in the same desperate, dismal state of mind. A priest met me at the doors who I had not seen for several years. Without any questions from me, he struck up a conversation with me and suddenly resolved all my problems. He told me precisely and directly what to do. With no exaggeration, this greatly decided my fate. Furthermore, doubts about the veneration of the royal family never arose again in my heart, no matter what examples of the weakness, mistakes, or sins anyone would cite to me concerning the last Russian emperor.

Of course, our individual religious experience without the confirmation of the Church matters little. However, fortunately for me, having canonized the Tsar Passion-Bearer and his family, the Church has given me a right to accept this small, unpretentious personal experience of mine as something real.

In my circle of friends, no one doubted that monarchy is the most organic and natural form of government for Russia. Nevertheless, we related skeptically toward the active and manifold monarchical movements of that time.

|

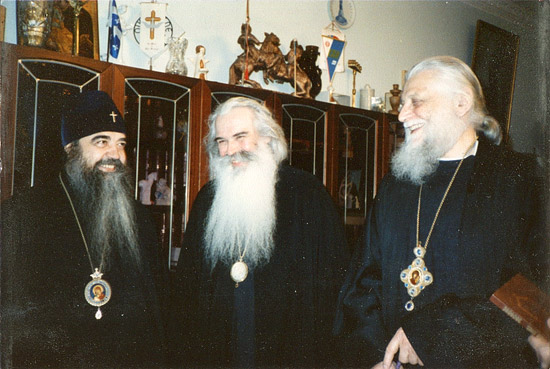

| Metropolitan Philaret (Bakhromeev), Metropolitan Pitirim (Nechaev), and Bishop Basil (Rodzianko). Photo by the author. |

These guests assured me that all of their decorations are in order, and they requested a meeting with the metropolitan without delay. To my surprise, Vladyka received them and listened to them attentively and without interruption for an entire hour and a half. The theme of their visit was simple—they were demanding that Vladyka aide them right away in the matter of a swift restoration of the monarchy. As Vladyka Pitirim was seeing them off, he said to them gravely, after thinking it over deeply:

“After all, if you’re given a tsar right now, you will shoot him all over again within a week!”

From that time on, whenever Vladyka Basil came to Russia he would call me ahead of time. He and I would joyfully set off together on another breathtaking adventure. Vladyka had loads of reasons for them; although strange as it seems, Vladyka never embarked upon a single voyage of his own will.

He told me one particular story concerning this.

In 1978, his wife, Maria Vasilievna died. Fr. Vladimir (as he was called then) was terribly shaken by his matushka’s death. He his love for her was boundless. It happened with him as it often happens with sincere Russian people—Fr. Vladimir started drinking.

|

| Vladimir and Maria Rodzianko on San Marco Square, Venice, Italy. Photo: bishopbasil.org. |

Fr. Vladimir started drinking in earnest. Although, despite his phenomenal health, enormous stature and strength, such drinking had to finally take its toll on his priestly duties as well as his work at the radio program. Batiushka consoled himself according to the Serbian custom, with raki, a strong, Balkan vodka. Who knows how it all would have ended, since neither his spiritual father, nor his relatives or friends could do anything with Fr. Vladimir, had not his matushka, Maria Vasilievna—a great ascetic and woman of prayer during her life—appeared to him from the other world and taken him in hand.

Fr. Vladimir was so stunned by this vision and his matushka’s exceeding sternness that he immediately came to himself, and that Russian illness left him immediately.

He stopped drinking, sure. But he had to somehow go on living. His children were already grown. There could be no thought, naturally, about a second marriage. Furthermore, if a widowed priest dares to enter into a second marriage after the death of his spouse, he is defrocked from the priesthood. But aside from that, Fr. Vladimir was so attached to his reposed matushka that the part of his heart that governs earthly love was occupied with Maria Vasilievna unto the ages of ages. Fr. Vladimir began praying fervently. He asked the Lord to send him some appropriate and saving consolation. And the Lord answered his prayer.

|

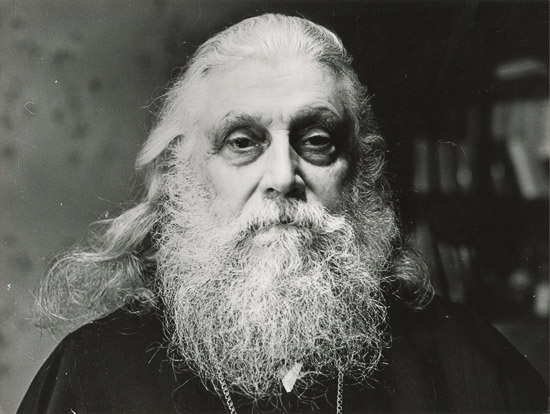

| Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh. |

It must be said that Fr. Vladimir knew full well that true hierarchical service was always bound up not with honor and rank, but with a multitude of everyday, never-ending cares, with the complete impossibility of belonging to oneself, and with an enormous burden of responsibility that is incomprehensible to the layman. Meanwhile, the fate of a bishop in the Russian emigration also meant being poor, even to the point of utter poverty. He was in his sixty-sixth year of life, forty of which he had already spent in service as a priest.

But Fr. Vladimir accepted the invitation to monasticism and a bishopric as God’s will and the answer to his prayer. He agreed cautiously… The hierarchs in America and England slapped his hands, and Fr. Vladimir’s lot was cast!

However, before his monastic tonsure, the future monk suddenly asked his spiritual father, Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh, an unexpected and simple-hearted question:

“So, I receive the tonsure from you, Vladyka. I take the great monastic vows before the Lord God and His holy Church. As for the vow of chastity—that is understood. The vow of non-acquiring is also clear. As for the vow of prayer—also. But I cannot understand a thing about the vow of obedience!”

“How is that?” Metropolitan Anthony said, surprised.

|

| In Donskoy Monastery. Photo: bishop-basil.org. |

“Be in obedience to every person you meet along your life’s path, as long as his request is according to your strength, and does not conflict with the Gospels.”

This commandment suited Fr. Vladimir’s soul right away! Although, the consequences of this constant readiness to resolutely and without unmurmuring fulfill this monastic vow was not always so easy to bear for those near Vladyka. Vladyka’s sacred obedience more than once turned out to be a veritable galley-slavery for me!

For instance, we are walking around Moscow. A rainy, nasty day. We are in a hurry to get somewhere. Suddenly, a babushka with a cart stops Vladyka.

“Ba-atiushka!..” she says in her trembling, elderly voice, not knowing, of course, that standing before her was no simple batiushka, but a entire bishop—from America, no less. “Batiushka, at least you help me—bless my room! For three years I have been asking Fr. Ivan to do it, and he just doesn’t come! Maybe you’ll have mercy, bless it, please?”

I have no time to open my mouth before Vladyka began pouring out the most passionate readiness to fulfill her request, as if he had been waiting all his life for the moment when he could bless this grandma’s room.

“Vladyka!...” I say with reproach, but already doomed. “After all, you don’t know where that room is! Babulya, where is it?”

“Not far—in Orekhovo-Borisovo! Metro Kashirskaya, and from there, forty minutes by bus! Nor far! the grandma joyfully informs us.

|

| Bishop Basil. Photo: bishop-basil.org. |

After our trek to the church, we descend into the metro at rush hour and ride to Kashirskaya station with several changes of train. Just as the grandma had promised, we squeezed into an overcrowded bus and jolted around for forty minutes to the final stop. Then finally, this descendent of the Princes Golitsyn, Counts Sumarokov, and Barons Meyendorf blesses that eighty-square foot room in a concrete panel Moscow high-rise; and he does it so inimitably prayerfully, magnificently, and solemnly, just as he always served. Then he sits down to table next to the happy grandma (they are terribly pleased with each other) and praises her offering—tea with pretzels and some old, crystallized, cherry jam complete with pits. Then he thankfully takes without refusal the ruble she stealthily pushes at the “batiushka” as we leave.

“The Lord save you!” says the old woman to Vladyka. “Now it will even be sweet to die in this room.” Time and again I saw how Vladyka Basil literally gave himself in obedience to every person that came to him, with an especial readiness and a foretaste of discovering something very important to him. It was clear that beyond his sincere readiness to serve people there was also some special motivation known only to him.

As I was writing these reminiscences, I recalled that the word “obedience” in Russian comes from the word “to listen.” Little by little, I began to guess that through this humble obedience Vladyka learned to hear and understand God’s will. From this his whole life became no less than a mysterious but constant and perfectly real conversation with God, a knowing of God’s providence, where God speaks with man not in words, but through life circumstances; and God thus grants such a person a great reward—to be His instrument in our world.