What do we know about the sixth continent other than that it is the abode of penguins and polar explorers, and that endless icebergs move around its shores like “ice mountains”, as they were called by the sailors on the “Mirny” and the “Vostok”, who discovered Antarctica? Many have heard something about the warm lake Vostok, conserved under three kilometers of ice, perhaps even retaining examples of flora and fauna that disappeared from the face of the earth eons ago, others may have read of the mythical Nazi base 211 hidden between the layers of ice on Queen Maude Land. In general Antarctica is shrouded in “ominous secrets”, and publications on these secrets have increased in recent decades. Aside from all this, the polar explorers themselves, in the words of Hieromonk Pavel (Gelyastanov) of Moscow’s Novo-Spassky Monastery who spent a year there, are skeptical about all these secrets. But this does not diminish the icy continent’s dark and menacing aura. And whether or not there really are gigantic quarries photographed by satellite in the seas of Bellinghausen, Admunsen, and Ross, with fireballs shooting out of the Earth’s longitudinal lines and leaving smoldering corpses in the snow, the icy continent remains a white spot in the direct as well as figurative sense.

The traveller who finds himself, not even on the continent, but at its threshold on one of its islands, feels like he’s on another planet; a planet where a steel rod shatters into pieces when it slips out of your hands in temperatures seventy below Celsius, and an incautious breath can frostbite your lungs; where the lights of the stations that lie beyond lengthy mounds shine an eerie green, and you can slice the kerosene with a knife like an aspic. It’s like outer space here, where anything can happen; and a winter here differs little from a stay on a space station or in the Martian desert.

King George Island, called “Waterloo” by Bellinghausen (Russian sailors, veterans of the Napoleonic wars, named the lands they discovered after famous battlefields), which has the least harsh climate, is called by the polar explorers, “the resort”. But even it is not without danger, even during the Antarctic summer, which comes in January-February.

“This is how it can be here,” said the guide of our tour around King George Island (Waterloo) Alexander, a surgeon from St. Petersburg. “A man goes to take out the trash—and he’s still taking it out. So do not separate from the group, please. This is Antarctica.”

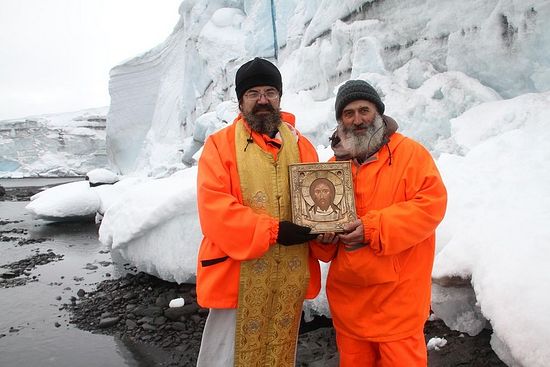

The biggest danger is the so-called “stone swamps”, which look no different from the surrounding landscape. There is no land there, only stone shards, hills, and gravel smashed by storm winds. That wet, brownish mush can suck a traveller down in the twinkling of an eye if he forgets to be careful. Therefore it is best to walk only with a guide and preferably with a walking stick, as you would in a marsh. Incidentally, our instructor and guide was the first Russian polar explorer to be baptized on Antarctica. Soon after the foundation stone was laid for the beautiful little church made of Altai larch and Siberian cedar now rising from the grim hill like burning candle, Igumen Georgiy (Ilyin) administered the sacrament of Baptism to him in a lake not far from the station, called by the inhabitants Lake Kitezh.

* * *

The craggy, blindingly white iceberg that rises to the skies and eclipses the horizon, weird chunks of cliff looming in the water along the shores, albatrosses and screeching seagulls, walruses, seal lions, seals, greenish-golden moss bursting forth to meet the sunlight, and of course the penguins themselves.

“They are so curious, so trusting; they are quite guileless, like little people; and your soul is refreshed with them, recalls Fr. Paul. If a polar explorer is in a bad mood he goes out for a walk along the shore, especially where the baby penguins are brought up, and the blues go away.”

Fr. Paul is a monk-extremist. Besides his winters in Antarctica, he also participated in the auto relay “Expedition Trophy” from Murmansk to Vladivostok—he was a crewmember for one of the off-roaders. From his youth he had always dreamed of going to the icy continent—something within the realm of possibility for the future meteorologist.

“After school I studied in the Maritime hydrometeorology institute in Tuaps, and my dream was to go either to the high mountain station of “Pamir”, or to Antarctica or the far north. Then this dream left me for a long time and there was no way to make it come true. But then I watched a film called, “A church in Antarctica” and thought, “Well how do you like that? Probably there are some higher-up priests going, and I won’t get in… Well, then Fr. Irenei came here, and he said, ‘The Holy Trinity St. Sergius Lavra is sending people there, and the dean is my friend. If you want, I’ll call him.’ I said, “Fr. Irenei, call him,” and then waited in fear and trembling for the answer. At the Lavra they were just then looking for a priest, because none of theirs was able to go. I went for an interview; they presented me to Archbishop Theognost, and then I found myself on Antarctica.”

Note: Archbishop Theognost of Sergiev Posad is the hierarch who on February 15, 2004, the feast of the Meeting of the Lord, consecrated the first and only Orthodox church in Antarctica on King George Island (Waterloo). It was then, during the Liturgy, that three broad rays of sun reached through clouds packed around the island. This episode was fixed in the film Even to the Ends of the Earth, filmed by the Lavra’s film crew. And it is also deeply symbolic that the 700th anniversary of St. Sergius of Radonezh coincides with the tenth anniversary of the consecration of the Antarctic church, which is sponsored by St. Sergius’s monastery—the heart of Orthodox Russia.

—Fr. Pavel, who are these people, the polar explorers? Are many of them religious? How was it for you to serve there?

—As you know, there are different people there every year. Therefore much depends upon who you end up with. For example, those who were there with Robert Scott perished, while all those who went with Admundsen survived. Or with Shackleton—his was a grueling expedition, but everyone survived it also. So, a lot depends upon the leader of the expedition.

—And who was the leader?

—I won’t say who. The general consensus was that it would have been tolerable if there were a different leader. The first thing he did was to take down the icon from the station refectory saying that there will be no icon while he’s there, but then during the winter through our common effort it was returned to its place. We said that we would fast, taking only water and not eating. He was in the main not a bad man, just a hardened atheist. But the polar explorers… My first experience communicating with them was complicated. Polar scientists are people who know a lot, and are very capable… Or, let’s say, a mechanic who participated in the sled expedition to “Vostok”… You can’t get through to them with only clever or kind words. Especially for those who have experienced much, risking their lives more than once, it’s not so important what you say as what you do, and what you in fact are. I remember how the polar explorers reacted to Hieromonk Kallistrat (Romanenko), now a bishop. He had just arrived and they needed to unload the ship; when they lowered the cargo to the Antarctic shores, he took off his ryassa and klobuk and was the first to start hauling the sacks. The explorers liked this. They thought, this is our kind of priest. He was also a sociable person, always able to hold a conversation. I have a different personality and was not as popular, but always tried to help according to my strength. Well, as for the scientists—they were not used to hearing that religion and science do not contradict each other, but that they to the contrary, compliment each other.

—I suppose they do not know very much about religion.

—That’s right. A lecture is held once a week, and one time they invited me to give it. I chose the theme of Russian religious philosophy: Berdyaev, Ilyin, the phenomenon of the Russian person, the Russian national idea… I wanted to say that Russia has a great mission, but when I began to talk about this I was met with a purely westernizing attitude. The feeling was that it’s high time to recognize Russia’s demise, there is nothing but drunkenness and dirt, and everything good we’ve ever had comes from the West. The discussion got heated, and it escalated into an indescribable nervous tension… Then one of them said to me that I needed to present the opposite view also, because for every scholarly argument there is always a counterargument.

—Well, yes, that is the human way of looking at it: there is a thesis, and antithesis, and synthesis. Did many receive Holy Communion when you were there?

—No, not many. Two received Baptism, but they received Communion irregularly. My assistant received Communion, also one ecologist from Vladikavkas and a coworker from the Chilean station, Eduardo, an Orthodox Chilean who married a Russian woman. The wedding sacrament took place in our church here… He works at the Chilean aerodrome, and is not a bad singer. We became close friends. Faith brings people together. People come closer not through nationality or culture as much as through faith.

* * *

In the film by Vladimir Soloviev “A Church in Antarctica” there are scenes where all the winter explorers—not only the Russians but also from the neighboring stations—ascend from the leaden gray valleys to the hill carrying a three-meter high cross. You can’t help recalling the common religious iconographic theme of “carrying the cross.” The cross itself is eight-pointed, strictly according to the Orthodox canon. It was made at the “Bellinghausen” station by polar explorers, from white pine, and this is the cross that was erected on the bare hill that can be seen from a distance both at sea and air. A higher will can be seen in this: our group was bringing a prefabricated cross from Moscow, but at a plane change in Paris it was loaded onto the wrong airplane. The polar explorers therefore had to make their own, which was heavier and simpler, but handsomer in its unvarnished, masculine simplicity.

Immediately after the Liturgy—the first ever Orthodox Liturgy to be served on the Antarctic continent—a procession with the singing of the troparia moved toward the hill over the shore dressed in that white Antarctic light that is like none other on Earth. And there we were on the top of the hill, where the wind immediately extinguished the candle lowered into the censor to light the coal. We guarded the relit flame with the palms of our hands—we were the winter polar explorers, Chileans, Germans, Spaniards…

“Bless, O Lord Jesus Christ our God, that the sign and power of Thy Cross might guard this place to the glory of Thee, our crucified God…”

The cameras flash, holy water splashes, and against the background of the gray dusk is seen the lemon yellow down jacket of Carman from Spain. The polar explorers.

Sunset in Antarctica. Photo: Hieromonk Gabriel (Bogachikhin)

Sunset in Antarctica. Photo: Hieromonk Gabriel (Bogachikhin) .

—Fr. Pavel, how can you explain their attraction to Antarctica? I’ve heard that many simply can’t live without the polar winter.

—I liked that the polar explorers, those who have spent many winters in Antarctica, call it the “white blond”. At first I thought, how is that? A blonde is white anyway… But it seems to me that this comes from a feeling of purity, incorruption. You know, the polar explorers never lock their doors when they go out, the doors are always open, no one would ever steal anything, and if anything should happen the Chileans and Uruguayans will share what they have with you. People are helpful and friendly.

—That is it—the polar fraternity? Does this have something to do with the nature there? It’s the craziest climate on Earth, completely unsuited for human habitation…

—It seems to me that life there is like life in a skete rather than in a monastery, when we spend time with the people. We lived on an island just a few steps away from the church; we served and prayed everyday, morning and evening. And we had the feeling that the church protects and preserves us. If here at home you have to force yourself to go to church, there you more often simply run there. No one made us serve the Liturgy; I and my assistant served practically alone, and we had the feeling that we had to both pray and receive Communion. And after Communion it was easier to endure all the hardships.

—I remember when the very idea arose of building a church in Antarctica. Many laughed—for whom, they said, the penguins? How would you answer that question?

—Originally its purpose consisted in at least keeping the Bellinghausen station open, because it was slated for closing. Perhaps it is God’s Providence, but after the church was built there, the government’s views on this changed abruptly, and expeditions increased there. For example, ships began travelling there from Germany with 200-300 excursionists, and the first thing people do when they step out of the dinghy onto the shore is to visit the church. It has become a calling card not only for the Russian Antarctic expeditions or the Bellinghausen station, but also for the entire island of King George. Foreigners are often in it. On Pascha (Easter) we had many coworkers there from the Chilean and Uruguayan stations, and even Chinese—the church was full. But as for the priest, his service should be something like what happens in the church that serves the cosmonauts in Zvezdny village (“Starry” village, just north of Moscow—a cosmonaut compound). The polar explorers, who like the cosmonauts are away from home and can’t return to their family and friends for as long as ten months, need similar psychological help. It would also be good to have a priest in the “Progress” station who knows all the polar explorers, and regular sessions connected with the stations and those polar explorers who want to talk with a priest. And perhaps it would be good to organize their visits, to hear confessions or give Communion to those who wish it, and to bless all these stations, when the airplanes fly or ships pass by all the stations. But unfortunately this has not been programed logistically.

—One would like to believe that a church in Antarctica is the beginning of a blessing of the entire icy continent discovered by Russian sailors. What do you see for the future of Orthodoxy in Antarctica? You said that you have given Communion to only a few. So, perhaps a church for the polar explorers is not really needed?

—If you take such polar explorers as the director of our station, then of course it’s not needed. But right after us there was another director. I will say his name: Oleg Sakharov. He, as I understand, chooses his own team. When we were already leaving, they came to the church. I announced that I would be serving a moleben of thanksgiving before boarding the ship; no one from our team came, but the new team did come, although Oleg Sakharov himself had not yet arrived. After the moleben of thanksgiving I served a moleben for the beginning of every good work. I blessed them, sprinkled them with holy water, and they were very joyful… Why not gather Orthodox scholars—oceanographers, glaciologists, meteorologists, mechanics, cooks, and doctors? It’s not such a complicated matter—an Orthodox station could be assembled, with an entire Orthodox collective. But as I was told in the Russian Antarctic Expedition, the head of the RAE will never go for it.

—Earlier you mentioned the Chilean, Eduardo, who married the Russian girl and became an Orthodox Christian. It seems to me that this is an amazing thing, and perhaps it was worth it to have a church in Antarctica.

—Of course. I think that this church’s parish is more than just the one or two people who come. Its parish is all those people who watch after this church. When I was there, I corresponded with many people; they wrote that they found a web camera that follows what goes on in Antarctica, and it films our services among other things. These are as if internet parishioners of our church. So, there is an interest not only among the polar explorers. I also think that our parishioners are also those who ended their lives in Antarctica. That is over 100 people. And when I read the prayer list, I get the feeling that they are waiting for this commemoration.

* * *

According to medieval sacred geography, the north is equated with a spiritual source, with paradise, while the south is its opposite, that is, the nether world. Now in the extreme South there is a Russian church, which was born from the idea of building a chapel in memory of those polar explorers from the Soviet Union, and later the Russian Federation, who died there. Fr. Paul affirms that they are all parishioners of this church—the only one there that serves the Eucharist, the sacrament of Thanksgiving to God, for Whom all are living. Added to the number of reposed parishioners for whom we pray in Antarctica was one more name—a cameraman of Russia’s Channel One, Anatoly Klyan, who filmed the laying of the foundation of the church on King George Island. Anatoly was killed last spring in Donetsk.

I remember him standing with his camera on his shoulder, pointed at the porthole of an aircraft carrier C-130. With these shots from the clouds of the wing and propeller of the military aircraft flying to Antarctica began within a few days the report of our expedition on the “Vremya” (“Time”) TV program. Two years later, the church assembled in the Altai and disassembled for its travel to King George Island, then reassembled from numbered logs, was consecrated by Bishop Theognost (Superior of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra) in the name of the Holy Trinity, although at first is was planned that it would be dedicated to St. Nicholas, the protector of sailors, and therefore also of polar explorers. But here is something symbolic: the only icon on the table that served as temporary altar was a small plastic icon that I had purchased the day before in Catholic store in Punta Arenas—the southernmost city of Chili and Latin America. It was a table icon of the Holy Trinity by St. Andrei Rublev. Symbolic. And the church in Antarctica, a church amidst an icy universe with the Southern Cross above it, is perhaps the best illustration for the last line of the Creed: “I look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the age to come.”

The contact information is at the bottom right corner of the page.