Source: Friends of Mount Sinai Monastery

April 10, 2016

When a tall monk approaches, just after the Six Psalms of the Orthros service and motions, “Pame, let’s go,” no time is to be lost. It is necessary to move quickly to claim a seat in the jeep waiting outside, or miss the experience of a lifetime – a journey into the monastic civilization of the seventh century. Liturgy is to be celebrated at the wilderness cave where Saint John Climacus lived as an anchorite for four decades. It was the ascetic feat that resulted in "The Ladder of Divine Ascent", a spiritual classic considered second only to Holy Scripture itself.

There is no conversation as the jeep moves through the darkness, down the long, dusty road to the monastery entrance, then onto the asphalt and past the slumbering hotels spawned by the 20th century’s surge in Sinai tourism. The driver turns right, and makes his way up an incline through a Bedouin settlement of cubic huts (furnished with satellite dish and color TV, if little else), and strains up the last stretch of access before it dwindles to a footpath trailing off into the mountains.

The jeep’s engine mercifully cuts off, and the Bedouin driver waits for all to climb out before returning to the Monastery. An unwelcome knot of anxiety develops as the monks silently fall in and, like infantry on patrol, move out in resolute cadence, swallowing distance with impervious disregard to detail like the treacherous gravel strewn over the path’s initial descent. The less sure-footed, partly from determination to appear equally nonchalant (more so from the knowledge that this path disappears further ahead), imitate the fast pace, with less success. The tall leader on the point, discerning the sound of shoes skiing downhill, instantly checks his pace.

One of the newer monks, as attentive as an experienced Bedouin guide, steps back to accompany the valiant but slower pilgrim contingent. As daylight breaks, the remainder of the hour-long trek passes with uninterrupted wonder at the awe-inspiring solitude of the scenic gorge.

Approaching the cave of Saint John, the silence of ages seems refracted by the soaring massifs extending the passage into an almost tactile iridescence. Evanescent shades of pink, blue, purple, red, and black granite - everything but gray - succeed one another, blended by the softly charged atmosphere into an impressionistic rendering of light.

About midpoint en route, an opening admits a path leading toward the left, toward the pretty hermitage of the Holy Unmercenaries, Kosmas and Damianos. The miracle-working physician saints healed without recompense, freely offering to God what they freely received. Their hermitage is situated in a closed valley so remote that one wonders if even its peaceful beauty could mitigate such isolation.

As the veteran monk in the lead, St. Catherine's Father Pavlos, reflected, "Here, in this stillness, you can hear your own heart beat. Of course the heart has first to be filled with the presence of God, because man is a social creature. If God has not first seized hold of a man's heart, it is impossible for him to endure stillness."

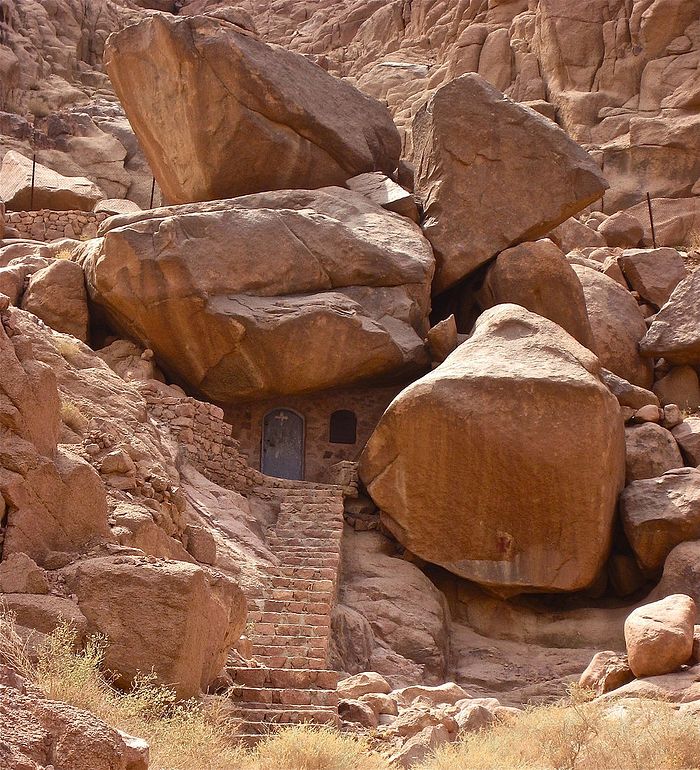

When the chapel at Saint John's cave suddenly comes into view this early morning, Father Pavlos calls a momentary rest by kindling a few dry brambles against the chill, observing, "Fire is a consolation in the desert." But the warmth dissipates as quickly as the flames, and within moments the chapel door has been unlocked, candles lit with pure olive oil replaced before their icons, and service books opened in readiness for the Liturgy.

The elder has disappeared into the altar. Communion bread and wine materialize in quick succession from his worn leather knapsack. As thick sheafs of names follow, monastics step forward to help commemorate them.

The byzantine Liturgy is introspective. Melodic prayer in evocative modalities awakens the heart. The absence of this world’s sentimental harmonies, and the harsh glare of its artificial light, rescue the soul from outer distraction.

Inner distraction recedes too, with the vision through the chapel windows of the “prism of eternity” without, this untouched primordial setting of holy endeavor. One cannot but wonder if saints concealed by its unwritten history are not invisibly present.

When Saint John Climacus was made abbot of the Sinai Monastery after his long sojourn here, a stranger in Old Testament raiment was noticed serving tables at the celebratory feast, energetically supervising cooks and stewards. Afterwards, when the visitor was nowhere to be found, John explained that “the Lord Moses” had done nothing strange in serving once more in the place where he belonged ...

Many decades earlier, when John was tonsured on the Holy Summit of Sinai, the Monastery abbot Anastasios predicted the twenty year old monk would one day take his place. Not long after, the renowned John the Sabbaite washed John's feet instead of his elder’s when they visited him, declaring he didn't know who the young monk was, but that he had just washed the feet of the Abbot of Sinai.

While someone reads the Thanksgiving prayers for the liturgist and others who received the Holy Mysteries, one of the Bedouin tribesmen who always seem to graciously appear at such junctures prepares a fire outside. He brews Greek coffee and Bedouin tea thick with sugar and the fragrance of wood smoke – and suddenly everyone is eminently ready for breakfast.

The providential leather knapsack appears once more, this time dispensing treats like canned dolmathes and crusty peasant bread. As its owner happens to be the Monastery gardener, some of ‘the best apples anywhere' may be on offer, even hand-made spanakopita, should anyone be newly arrived from Greece (or if any daring monk has been in the kitchen recently).

With a glance toward Saint John's cave during the coffee hour, Father Pavlos recounts how fervently the Saint prayed there upon receiving the revelation that his disciple monk Moses was in mortal danger: the rock Moses was resting under from his labors at another hermitage was about to collapse. The sleeping monk suddenly heard his elder's voice warning him, and escaped to safety just as the enormous boulder came crashing down.

This beautiful place has much to say of the freedom won by those who met its challenges with faith alone. Saint John’s biographer identifies his greatest acquisition as holy and precious humility, 'the queen of virtues'.

Exile is a separation from everything, in order that one may hold on totally to God. - Saint John Climacus

John himself describes indefinable humility as 'a nameless grace in the soul, nameable only to those who have tasted its experience' – one which brings the unspeakable wealth of God directly into the soul.

'For it is said,' John concludes, 'Learn not from an angel, not from man, and not from a book, but from Me, that is, from My indwelling and illumination and energy in you, for I am meek and humble in heart, and in thought, and in spirit, and you shall find rest from conflict, and relief in your souls from thoughts.'

Too soon, Geronta Pavlos announces departure; a new workday is beginning back at the Monastery. Unteachable secrets of blessed exile have stunned hearts on this immortal morning - now it's time to hold on, totally.