Source: Theology That Sticks

February 25, 2016

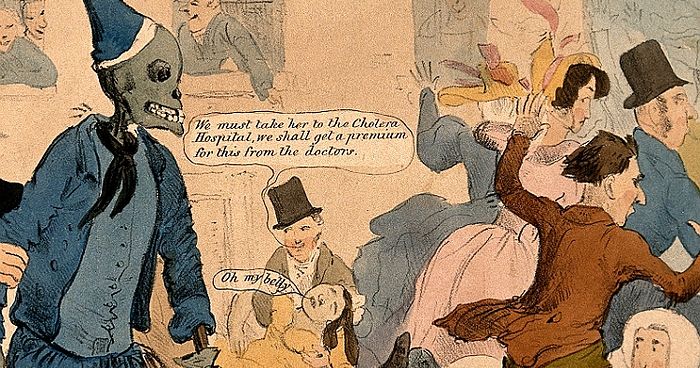

The Zika virus is spreading like wildfire and now threatens to infect half the western hemisphere. The stock market will collapse, ruining the economy, leaving us all destitute, homeless, and hungry. Terrorists and migrants will overrun our borders, blow up our restaurants, steal our jobs, and destroy our culture.

Plague, mass shootings, famine, war, Netflix outages. . . . Pick your panic. We live in a bramble of fears. We have anxiety about our families, worry about our jobs, and concern about our futures. Fear drives entire industries, propels our politics, and keeps us in a state of perpetual agitation.

Why are we so susceptible to this?

Sharing is (not) caring

Emilio Ferrara, a University of Southern California computer scientist, studies fear trends. Remember the Ebola scare in the fall of 2014? Within weeks of the nation’s first reported case, Americans ranked it among their top healthcare concerns. Meanwhile, the pandemic never materialized. By then the U.S. Centers for Disease Control had confirmed just four cases.

Mining Twitter, Ferrara found “fear-rich” tweets went viral while the actual virus didn’t. The only outbreak was fear-induced stress. The reason?

“When we hear or read about a threat,” says Adrienne Berard in an article for Nautilus, “our bodies respond to it as if it were real before our conscious minds can evaluate its truth. And because we feel threatened, we’re more likely to believe that we are, and to share our fears with others.”

Berard mentions a 2012 study analyzing the email shares on New York Times articles. The most shared stories, she says, “tended to evoke ‘high-arousal’ emotions such as awe, anger, and anxiety.” I’m guilty of this. Check my Facebook or Twitter feeds. I’ve shared plenty of bad news over the years.

Our creatureliness explains why we find ourselves enmeshed in this thicket of anxiety. It’s a survival mechanism. Vulnerable to life’s vicissitudes, we face a future with a million possibilities, some of them dangerous and threatening. Natural responses to this reality range from conservatism and caution to fear and dread.

Add news media and social sharing to the mix, and we can quickly find ourselves entangled. There are things I don’t even know to be scared about. Matt Drudge—and all my friends—will fix that by nine this morning.

The stories we tell ourselves

To compound the problem, we cope with uncertainty by settling things in advance. Consciously or unconsciously, we believe mentally preparing for the worst limits our vulnerability. We spin stories about the future, imagining different scenarios, sometimes piling one upon another. We take supposed information about our safety, our health, our finances, our relationships, whatever, and knit together a narrative that gives it all direction and meaning.

Zika, terrorism, the election, our boss’s raised eyebrow, the discomfort in our gut, the evasiveness from our spouse—whatever’s going on, we think we can finally find certainty, resolution, answers, calm.

But it doesn’t work. Usually our stories are wrong. And if we are right once, what about the next time? And the times after that? We see a few data points, maybe dozens, but there are countless others that we cannot see and know. Beyond that, assuming we had all (or even more than a few) of the facts, our ability to synthesize and formulate predictions is anything but absolute. We drive ourselves to despair and panic just trying.

Isn’t this why Christ says to take no thought for tomorrow, that the present day has enough troubles of its own? He’s not saying to eschew planning or preparedness. He’s saying not to live in a future that hasn’t yet arrived, one about which we are prone to fret and worry.

The Apostle Paul gets at the same point when he tells us to be anxious for nothing, but go to God with prayer and thanksgiving. He urges gratitude for the moment and trust for tomorrow. Why? Because God is involved in history, our history. “The Lord is at hand,” says Paul. He will close all the open loops and resolve all the unanswered questions.

Don’t buy it

Our imaginations lead us astray. We fabricate a thousand stories and then live in function of our fantasies, tormenting ourselves in the process. When we do this, we show ingratitude for the moment (because we’re obsessed with the future or some alternate reality, not the present reality we possess by God’s grace) and a lack of trust in God (because ultimately, the future is in his hands, not our heads).

Whatever survival benefit we gain from fear-induced stress, it hardly compensates for the emotional and spiritual turmoil we suffer in exchange. We can’t get away from fear-mongering pundits, politicians, activists, and trolls. But we don’t have to buy what they’re selling.