As the Sunday of the Holy New Martyrs of Russia approaches, we present the story of a man who also suffered for the truth in the soviet gulag, related by the doctor who treated him in the prison tuberculosis ward.

1. The Steppe and the Camp.

|

| Steppe. |

The camp hospital consisted of three small houses on the edge of the parcel, built of home-made clay and straw bricks. I was the director of this hospital, and its only doctor.

A patient’s words had caused my anxiety. That morning, as I was leaving the ward after rounds, he summoned me, and with facial expression unusual to him, asked, “Will you be returning today, doctor?”

“I will return in the evening. I must go to the dairy farm this afternoon.”

“Will you be returning late?” He had never asked me like this before. In fact, Basil had always been rather silent.

“No, not late, about 8:00. What do you need? Do you not feel well?”

“No, I am fine. Do not worry. I need to give you something.”

“Can’t you give it to me now?”

“No, but if you come at eight, that would be good.”

It happened that there were many sick people at the farm. I tried not to take too long, but there was no time to think and now I was becoming more and more overcome by anxiety.

Basil Sokolov had been a front-line soldier, and was still quite young. He had been sent to the camps straight from the front. He told me that he had always been a jolly fellow from childhood—he played the accordion well, and like to play at weddings. At the front he played in soldiers’ concerts. Once as he was hanging portraits in the clubhouse he hung Stalin’s portrait in the wrong way, then made some remark in that regard. He was arrested the next day, and given the standard sentence of ten years of reformatory labor camp according to the 58th statute for anti-soviet agitation (tenth paragraph).

He had been in the komsomol, and was a wood-worker. Before the war he had worked in Kirovgrad, and knew how to make delicate items out of wood. His father, also a wood-worker, had trained him to labor. He lived with his parents and large family. When the war broke out he landed in the army as a volunteer almost from the start, during the eighteenth year of his life. After he was sentenced, he was sent to cut trees in the far north.

The joyful spirit of this defender of the Fatherland, victor over fascist aggressors, and gregarious accordionist, was speedily destroyed by oppression, hunger, and cruel fate; the more he tried to fight, (as at first he did), for justice, the more speedily he was crushed.

He was crushed by scurvy, dystrophia, pellagra (an inflammation of the skin common in the far north). He was no longer able to labor, and so they beat him. He was beaten in the darkness of the barracks as they kicked everyone out to work, making no attempt to discern the reason for any delay. Foremen and brigadiers, chosen from amongst the criminal element, beat all the others.

The barracks were cold, and the weather outside severely cold. This led to the tuberculosis ward. “They beat us on the lungs and then wrote ‘tuberculosis’,” said the patients. In the summer of 1974 Basil found himself in a prisoners’ convoy to the southern camps, and arrived at our agricultural camp for rehabilitation together with other over-worked prisoners. His tuberculosis was widespread and aggressive.

The camp was small-scale agricultural; it had its own granary, vegetable garden, melon and squash field, and dairy farm. I was able to get food for patients beyond the meager camp rations. Using the hospital tractor which carried food products to the hospital kitchen—and which also carried the dead to the cemetery—we, the hospital personnel together with recovering patients, dug a large garden, which was the hospitals’ own agricultural territory. Thus, without x-ray equipment, respirators, or medicines (other than the most primitive and specific) did our patients recover on potatoes, peas, and beets. No one in the cities could believe our results.

But what fine air we had! The little hospital houses stood on the shores of a steppe river. Beyond the river lay a limitless steppe stretching many hundreds of kilometers. Yes, miraculous cures took place there.

“The main thing,” said the patients, “is to turn the illness around, and then everything will get going in the right direction!”

In order to turn the illness around they had to have something even more necessary than medicines. We had to create a peaceful atmosphere, remove the stone that oppressed their souls, banish the thought from out of their consciousness that they were humiliated by imprisonment, deprived of human rights and dignity. We had to create an atmosphere of care for them, good will towards them, respect, emotional warmth, some at least primitive coziness, surity of their firm protection, and even love for them. We also had to create our own joys and entertainments. This was not easy, but nevertheless we achieved it. My brain worked day and night to achieve this aim. The main problem was proving to the administration that it was actually in their own interests to simply waive their hands at me and turn a blind eye to my order in the hospital. I had to become needed to them. When two directors received awards for reduced mortality it became much easier for me.

2. Basil Sokolov.

Basil Sokolov was twenty-seven years old. He was particularly able to win people’s hearts, and the patients always remembered him. He was ever serious, and at the same time amiable and affectionate, calm and satisfied with everything, always inwardly joyful. He attracted people, and they would become attached to him. Patients of all categories loved him—political and criminal, young and old. The hospital personnel also loved him. People came to him for advice, and when they received letters, sad or happy, they shared them with him.

In the winter, when our houses were covered with snow, he would lay there for long periods of time, as if thinking something over, reminiscing.

In the summertime he liked to sit by the bank of the river and watch the water. He never took part in other patients’ noisy joking and conversation. He read much. He never received letters nor did he write them, although his parents were still alive. “It’s better that they not know where I am or what’s become of me,” he said to me. “And if I remain here, let them think that I died at the front. It will be easier for them.”

This was understandable. He never worried about anything, but to contrary, always assuaged others’ anxieties. In his radiant joy, his stride, his deeds, his eyes—the clarity of his gaze, was hidden a mystery; he literally carried within himself something which he loved and cherished, venerating it and rejoicing over it.

When people came to him he responded with joyful readiness, as if he were eagerly anticipating them. They would ask him questions, he would answer them, and everyone would depart encouraged about something.

What attracted people to him so? I myself experienced this. Oh, what wouldn’t I have done to save him! As I walked, I thought about how everything that we now see but do not understand will someday be explained and clear, but we will never understand people if we do not make it our rule to remember that some peoples’ eyes are blinded, while others’ see all in a bright light that shines before them; and that truth and true happiness have no clear outward distinction amongst everyday realities, but can only be recognized in the radiant light of the soul.

But where did Basil get this? One month ago he had tracheal bleeding which was not repeated. He felt significantly better. Just a few days ago he had given one of the patients a very beautiful chess set which he had carved out of wood.

Could it be that he was feeling badly, and felt trouble ahead? That would explain why he wanted to see me a second time that day. Probably he was very agitated yesterday, although he did not betray it outwardly. He even comforted me. Could this have played a part in his condition? The matter was that the head of the sanitary unit, a hired paramedic, a proven worker and lieutenant of the medical-sanitary service of the NKVD, had received another of a number of reports against me in which Basil’s name was mentioned. It was written that I was keeping Basil in the hospital although he was perfectly healthy, that he had “stuffed himself,” that I was fattening him up and even prescribing extra food for him. This was obviously written by some guileful and angry man in an attempt to play up to the authorities. He was not the only one who foamed at the mouth and lost his composure over the humane atmosphere in the tuberculosis ward, it’s “free spirit,” which seemed to go against the rules and regime. As for me, I often experienced heavy pressure from the stalwarts of the regime against this spirit. I had become toughened in this battle, and learned how to maneuver.

I was able to hold my position, but the reports continued to come. No one paid any attention to them, but all the same, I could never be sure that they would cease. The contents of these reports never differed. They always wrote that half of my patients were well; that I detain my favorites and do not write their releases; that the majority of my patients have very long prison sentences; that I harbor and coddle traitors of the Fatherland; that I create conditions for the patients as if they were free men; that communication in the hospital is built upon such phrases as “would you be so kind,” and “if you please”; that I had opened a resort for the prisoners, with various procedures in the sun and shade; that I had instituted the celebration of patients’ birthdays, and that on those days pies are baked and other pleasures provided. Names were cited and examples recounted.

It had been very difficult to save Basil from death. And now the director of the sanitation department had the idea of calling me and Basil into the sanitation unit with his case history in order to review the warning—that is, the report. Oh, why did I take him there? Why did I carry out the director’s request? He should have come to the ward himself. They are all afraid to come to us, afraid of being infected with tuberculosis in the wards. One of the prisoners’ doctors once said to me, “I can understand, colleague, why you prefer the company of tuberculosis patients over that of the authorities. It is because the authorities are much worse, more dangerous and repulsive that the tuberculars.”

But Basil answered the directors’ questions on his own behalf as well as mine, and with such composure and dignity! When he was asked, “Well, Sokolov, aren’t you felling well already? Couldn’t you have requested a release?” he replied, “I would never ask to be retained, neither would I ask to be released from the hospital, because I know quite well that only Marina Sergeevna knows what needs to be done with the patients, while our subjective sensations are very deceptive and often change.”

“Listen to the patient yourself,” I said, “here is my stethoscope.” “Bring some alcohol from the bandage department,” the director said to an assistant. He wiped the stethoscope with alcohol and pronounced importantly, “Undress. Breathe.”

“Under the left corner of the scapula is a sharp, windy, cavernous sound,” I said, by way of assistance. “Above that is widespread wheezing,”

“Yes,” the director said with deep thought, and once again pressed the stethoscope to Basil’s scapula, where nothing could be heard at all. “You may depart to the corridor, Sokolov, but you, Marina Sergeevna, remain here.”

Then a ludicrous conversation ensued, instructing and warning me, concluding in a command to take him off the supplementary nourishment.

I made no reply, repeating only “alright,” although I never did what he said. This, they understood. But could it really be that all of this had an effect upon Basil? Why did he ask me to come again that day at eight o’clock in the evening?

I was almost running back to the ward. Upon arrival I quickly put on my doctor’s coat and went with the shift nurse on rounds, beginning with the room where Basil lay. He was pale, but he looked at me and smiled. The nurse told me that after lunch, he had experienced a slight coughing up of blood.

“Well, Basil my dear,” how do you feel? Now we are going to give you an IV.”

“I feel fine,” he said, “You can skip it.” “No, the night is still ahead,” I said, “It’s better that we do it.

“Well, alright, I’ll rest a bit after the IV, and you come back to me after finishing the rounds, please. Alright?” “Alright,” I answered.

3. Remember the Lord!

After my rounds I went alone, without the nurse, and sat down near Basil. There was no patient in the bed to his left, and from the bed to his right the patient arose and left the room. We were now alone.

“I want to give you something,” Basil said, “It is a poem, only without rhyme. It’s not mine, but it is very dear to me, for it turned me around—not immediately after reading it, but gradually. It carved its way into my soul, and made me think. Reading many wise books also helped. I want you to have it. I’ll tell you a little about it. After a heavy battle in 1944 (I thought that no one would be left alive)—it is terribly difficult to recall it—I and only a very few were by some miracle left alive. The sanitation instructor found a slip of paper with poetry in the coat pocket of one young soldier. Many of us read it. It touched me immediately; I kept it, and many others later copied it. Only, this one I am giving you is not the original, for that was taken from me when I was put into prison, and I now have written it down again from memory. I had learned these lines right away by heart. The poem was signed: ‘Alexander Zatsepa.’ Here, take it.”

“Why are you in such a hurry, Basil? We are not separating.”

He lowered his eyes. I again felt strange. “How are you feeling?” I asked. “Fine, right now, very fine. Good night Marina Sergeevna. Thank you for everything.” “Good night to you, Basil,” I said, “I still have to sit and work; I have case histories to write.”

“Oh, how good it will be for me to sleep,” he again smiled joyfully. I left.

I decided not to read them right away, otherwise I would get lost in thought once again, and once again I would fail to finish the case histories I had already put off for several days.

That night the nurse came running in, saying, “Marina Sergeevna, Sokolov is in bad condition. He’s dying.”

Running into the room I saw the shift nurse standing next to Basil with an empty syringe, and Basil was already dead; but no, not dead, for when I took his hand to check his pulse and called “Basil, Basil!” the corners of his mouth quivered and parted into a smile, and this smile remained on his face. This could not have been my imagination. It really happened! Finding no pulse or breathe in him, I closed his eyes.

The nurse told me that he had begun again to cough up blood. He was very weak, but nevertheless he carefully spat out the blood so as not to stain the bed sheets. She had succeeded in administering medicine to stop the bleeding, but he suddenly sat up in the bed, straightened himself, and pronounced with a full voice so loudly that the patients in both adjoining rooms heard it and woke up, “Remember the Lord!” He then raised his hand, blessed everyone, and fell back upon the pillow.

The nurse broke into tears.

4. Alexander Zatsepa.

I went into my office, threw open the window, and sat down at the table. Outside it was already getting light. I took the poem Basil had given me out of my pocket and began to read. Alexander Zatsepa had artlessly directed himself to the One to Whom he was directing himself for the first time in his life, and in this was contained an awesome power. I read:

Listen, God… not once in my life

Have I spoken with You, but today I wanted to greet You.

You know that from my childhood days I was always told,

That You do not exist. And I, a fool, believed it.

I never contemplated Your creation.

But tonight I gazed

Out of the crater that a grenade had blown,

At the starry sky that was above me.

I suddenly understood as I admired the twinkling,

How cruel a deception can be.

I do not know, O God, if You will give me Your hand,

But I will tell You, and You will understand me.

Isn’t it strange that amidst this horrible hell

The light was suddenly revealed to me and I beheld You?

Besides this I have nothing more to say,

Only that I am glad that I have seen You.

At midnight we are supposed to attack.

But I am not afraid—You are watching over us.

The signal. Well, I am supposed to start out.

It was good to be with You. I also want to say,

That as You know, the battle will be vicious,

And, perhaps I will be knocking at Your door tonight…

Although up to now I had not been Your friend,

Will you let me in when I come?

Well, it seems I’m weeping… my God, You see,

It has happened that I have beheld…

Farewell, my God, I am going, and am unlikely to return.

How strange it is, but now I do not fear death.

(Alexander Zatsepa)

I did not wipe away my tears, they ran down my neck and under my collar. Soon it was completely light outside and I put out the lamp, but I did not rise from my chair.

“In the selfsame hour, Thou didst vouchsafe, O Lord…” the words from the song about the good thief, whose eyes were opened on Golgotha, rang in my ears. Alexander Zatsepa’s eyes were also opened in the very hour before death to: “how cruel a deception can be.” “The Light suddenly appeared to me!” he said. How miraculous! And in that brief hour, so significant for him, so earth-shaking, he does not want to remain alone with his joy, or keep it all to himself. No, he wants to share it, to give it to others. He is afraid to take it with him. He searches his pockets for a pencil; he finds one. He writes inspired lines. So that the slip of paper would more readily be found, he places it in his outer-most coat pocket—or perhaps be hadn’t time to hide it better?, Alexander wrote these lines during the very last minutes of his life.

Basil received it all from him. He had said, “I do not know by what miracle I remained alive.” Then, after the battle, what a path of suffering he had to travel, what a Golgotha. And how high he had ascended the spiritual ladder—so high! Yes; and perhaps he was not the only one?

I went to the women’s quarters and gave them some dark cloth from which to sew a shirt for Basil, and some gauze for a shroud. Then I went to the construction section and said to the foreman, “You are going to receive an order for a coffin from the sanitation section. I ask you to make a real coffin, a good one—not the kind that you make from rough, splintering boards with cracks throughout. A holy man has died in my hospital.” The foreman answered, “I have just the material needed right now, and I’ll ask a good craftsman to make it.”

5. Fr Arseny.

Afterwards I went to the prisoners’ zone. There, in the common barracks lived a seventy-four-year-old hieroschemamonk, Fr. Arseny, with a twenty-five year sentence. Before he was arrested in 1945, he had lived twelve years in the mountains of Sukhumi, in Svanetia, Georgia. There he had no contact with people other than three or four times a year, when he descended into the village for necessities (lamp oil and salt). He was living in a cell that he had built with his own hands. In 1945, the authorities began capturing those people who had been hiding from them in the mountains for a period of time. Not knowing what was going on, Fr. Arseny descended the mountain and fell into an ambush. He had no papers, no work, and no pension. He was tried and sentenced to twenty-five years of labor camps.

I told him about Basil. He made a band to be placed upon his forehead, and wrote the prayer of absolution. He explained to me what to do. He said that he would serve a funeral and pannikhida. He blessed my hands, transmitting through them a blessing to Basil, saying, “Bury him.”

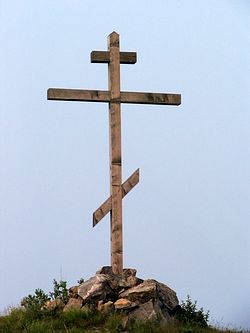

A pick-up truck from the construction section carried the coffin covered with rush mats so that it would not attract attention by its unordinariness (for, the coffin was an Orthodox one), together with a beautiful wooden cross. I had not even mentioned a cross to the workers…

The driver said, “I can’t go to the cemetery right now. I was told to bring a gas tank to the yard right away.”

I rejoiced. How wonderful! There was still much to be done with Basil, and many would want to come and say their farewells to him. If the sanitation division were to see a truck standing for a long time outside the morgue, they would come out to investigate.

Basil lay all clean and dressed as if he were a free man. He was handsome. His lips were touched by a smile. Quietly, all those who had know him came to say good-bye. They walked along a low, unnoticeable path. One by one they walked up, removed their hats, and without lingering, looked around and continued on, allowing the next person to come. Workers came from the building sector. I stood by the window, watching the whole time.

The truck could by seen driving up. I went out and did everything to Basil that Fr. Arseny had instructed me to do. Then I said “close the lid.”

The coffin and cross was again covered with rush mats. The old paramedic came to conduct Basil to the cemetery. The workers dug a deep grave. They carefully lowered the coffin, then covered it with earth, and planted the cross. They covered the large mound with sod from a nearby ditch. I gave each worker a little bottle of spirits and a packet of food as a remembrance of him for their prayers, and they were pleased. Everyone departed.

6. Basil’s cross.

The old paramedic took out a blue notebook and began to read a prayer. I sat down on a nearby mound and looked out over the steppe at the sky and the grave mounds of deceased prisoners. It was a scene that I will never forget to the end of my days, which shook me to the very soul. Stretched out upon the vast expanse of barren steppe was one mound after another, like hillocks, and upon each one stood a placard with a number—the prisoner’s personal number. These numbers were written on the prisoners’ records. They were also printed on the envelopes addressed to relatives, waiting long for a letter…

Then I began to ponder that now, in the barracks of the prisoners’ zone, in a dark corner, the saintly schemamonk was serving a funeral and pannikhida for slave of God Basil. How could it be that everything had come together so well today? Here, in a prison camp, we, by the elder’s powerful prayers, had been able to bury him according to the Christian custom without being discovered.

It became perfectly and distinctly clear to me how miraculously the Lord had revealed His will toward Basil, who deserved such mercy! I had acted almost mechanically. I went here and there, said a word or two without forethought, and everything happened as it should have. I felt somehow joyful that I had been, at least to some small measure, the instrument of God’s will. I glanced at the tall, beautiful cross over the grave, then out upon the boundless steppe all around.

|

A light breeze was blowing. The sun came out. I thought about the rays that would shine over Basil’s grave, and again my gaze rested upon his cross. Peace and joy began to penetrate my heart, and suddenly I saw the grave-yard in a completely different way. I saw that the cross stood not only over Basil’s grave, but over the entire cemetery. I saw that his high, green grave was the pedestal beneath the monument which united all the hillocks and placards, protecting them and preserving them from destruction and oblivion, and that in the singing of the birds rang out Basil’s final words, “REMEMBER THE LORD!”

Such harmony and wisdom can be found in every corner of the earth, in the great and the small, in every tiny note of every singing bird.

For two thousand years, mankind has now fallen on its knees before, now crucified over and over the One who has revealed to men the mystery of Divine wisdom; the One Who has shown by His example that after Golgotha comes the resurrection which conquers death, the Feast of feasts and Triumph of triumphs. The triumph of love! Oh unfathomable mercy! Every hour, it nudges forward those who have become lost on life’s path, the misfortunate and sick, towards the healing springs! Today the Lord has lifted the veil and shown how eternal is His love, and how unshakeable and eternal His justice!

A bird flying by chirped, as it were, into my very ear. Over the earth and its grave-mounds, in the bright setting sunlight, the day’s heated air shimmered like a bright aurora, like someone’s pure breath…. And Basil Sokolov’s words sounded out, “REMEMBER THE LORD!”

By C. C., Russky Palomnik, No.28, 2003.

Translated by Nun Cornelia (Rees)